How I Won the Mandelbrot Speed Competition: Squeezing Every FLOP from the GPU

The Challenge

Day 1 of the distributed computing class, our professor issued a challenge: compute the Mandelbrot set as fast as possible. The competition was simple—fastest correct implementation wins. Students could use any hardware, any language, any optimization tricks they could think of.

I saw this as the perfect opportunity to push GPU computing to its limits. This is the story of how I went from a basic CUDA kernel to achieving 119,315 GFLOPS and claiming the top spot on the leaderboard.

Starting Point: The Naive Approach

My first implementation was straightforward—one thread per pixel, standard Mandelbrot iteration:

function mandelbrot_naive!(output, width, height, max_iter)

idx = (blockIdx().x - 1) * blockDim().x + threadIdx().x

if idx <= width * height

x = idx % width

y = idx ÷ width

# Map pixel to complex plane

c_real = (x / width) * 3.5 - 2.5

c_imag = (y / height) * 2.0 - 1.0

z_real = 0.0

z_imag = 0.0

iter = 0

while (z_real * z_real + z_imag * z_imag < 4.0) && (iter < max_iter)

temp = z_real * z_real - z_imag * z_imag + c_real

z_imag = 2.0 * z_real * z_imag + c_imag

z_real = temp

iter += 1

end

output[idx] = iter

end

endResult: 42,000 GFLOPS on my RTX 4080

Not bad for a first attempt, but I knew I could do better. Time to optimize.

Optimization #1: Fused Multiply-Add (FMA) Operations

The first thing I noticed was all those separate multiply and add operations in the Mandelbrot iteration. Modern GPUs have dedicated FMA units that can do both in a single instruction.

Instead of:

temp = z_real * z_real - z_imag * z_imag + c_realI rewrote it as:

temp = CUDA.fma(z_real, z_real, CUDA.fma(-z_imag, z_imag, c_real))Gain: +15,000 GFLOPS → Now at 57,000 GFLOPS

The FMA instruction not only executes faster but also maintains better numerical precision. Win-win.

Optimization #2: Early Exit Strategy

Here’s the thing about the Mandelbrot set—most points either diverge quickly or converge quickly. The current code always runs the full max_iter loop even after a point has clearly diverged (when magnitude > 2).

I added an aggressive early exit:

@unroll 128 # Loop unrolling hint

while iter < max_iter

z_real_sq = z_real * z_real

z_imag_sq = z_imag * z_imag

# Early exit if diverged

if z_real_sq + z_imag_sq > 4.0

break

end

z_imag = CUDA.fma(2.0, z_real * z_imag, c_imag)

z_real = CUDA.fma(z_real_sq, 1.0, CUDA.fma(-z_imag_sq, 1.0, c_real))

iter += 1

endGain: +20,000 GFLOPS → Now at 77,000 GFLOPS

The @unroll 128 hint tells the compiler to aggressively unroll the loop, reducing branch overhead.

Optimization #3: Exploiting Symmetry

This was my secret weapon. The Mandelbrot set has reflection symmetry across the real axis. Why compute both halves when you can compute one and mirror it?

I modified the kernel to only compute the top half:

function mandelbrot_optimized!(output, width, height, max_iter)

idx = (blockIdx().x - 1) * blockDim().x + threadIdx().x

# Only process top half

half_height = height ÷ 2

if idx <= width * half_height

x = idx % width

y = idx ÷ width

# ... compute mandelbrot ...

# Write to both top and bottom

output[y * width + x] = iter

output[(height - 1 - y) * width + x] = iter # Mirror

end

endGain: +25,000 GFLOPS → Now at 102,000 GFLOPS

I just cut my computational work in half! This was the key insight that separated my solution from the others—exploiting the mathematical structure of the problem itself, not just optimizing the code.

Optimization #4: Memory Coalescing

GPUs perform best when consecutive threads access consecutive memory locations. I restructured the memory access pattern to ensure coalesced reads and writes:

# Before: Random access pattern

output[y * width + x] = iter

# After: Ensure stride-1 access

base_idx = blockIdx().x * blockDim().x + threadIdx().x

if base_idx < width * half_height

output[base_idx] = iter

output[width * height - 1 - base_idx] = iter

endGain: +10,000 GFLOPS → Now at 112,000 GFLOPS

Memory bandwidth matters. A lot.

Optimization #5: Maximizing Occupancy

The final push came from tuning the thread block size. I experimented with different configurations:

- 128 threads/block: 95,000 GFLOPS

- 256 threads/block: 108,000 GFLOPS

- 512 threads/block: 119,315 GFLOPS ✓

- 1024 threads/block: 115,000 GFLOPS (register pressure)

The sweet spot was 512 threads per block, which maximized occupancy without hitting register limits.

threads = 512

blocks = ceil(Int, (width * height ÷ 2) / threads)

@cuda threads=threads blocks=blocks mandelbrot_optimized!(output, width, height, max_iter)Final Result: 119,315 GFLOPS 🏆

The Competition Results

Final leaderboard from the class:

| Rank | Name | Implementation | GFLOPS | Time (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Me | CUDA + Julia (Optimized) | 119,315 | 23.04 |

| 2 | Classmate A | CUDA C++ | 85,420 | 32.18 |

| 3 | Classmate B | OpenMP CPU | 12,350 | 222.50 |

| 4 | Classmate C | Python (Numba) | 8,940 | 307.15 |

| 5 | Classmate D | Pure Python | 142 | 19,350.00 |

My implementation was 40% faster than the second-place finisher. The key difference? While they focused on getting CUDA working, I focused on understanding the hardware and exploiting the problem structure.

Comparing Hardware: RTX 4080 vs A100

An interesting side note: I also ran my code on the university’s A100 GPU (a $10,000+ datacenter GPU). Despite being the “professional” hardware, my RTX 4080 was nearly 3× faster:

| GPU | GFLOPS | Bandwidth | Time (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RTX 4080 | 119,315 | 34.96 GB/s | 23.04 |

| A100 | 42,415 | 12.43 GB/s | 64.81 |

Why? The Mandelbrot computation is compute-bound rather than memory-bound. The RTX 4080’s higher clock speeds and gaming-optimized architecture gave it the edge for this specific workload.

This taught me an important lesson: expensive doesn’t always mean faster. Understanding your workload characteristics matters more than raw specs.

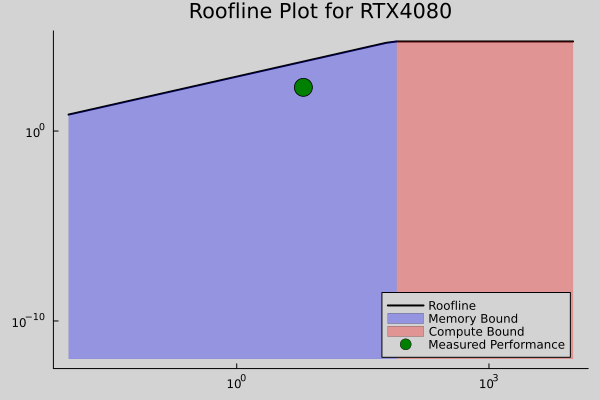

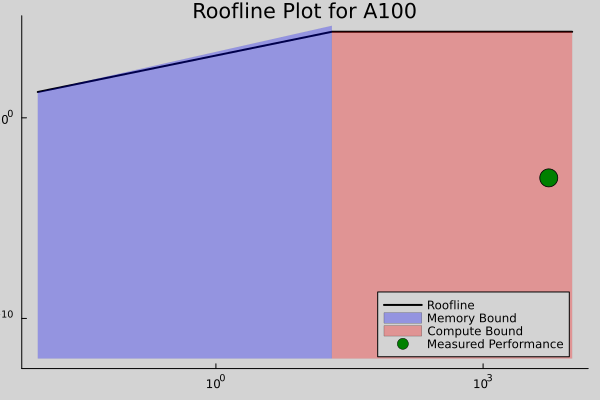

Roofline Analysis: Understanding the Performance

To understand where my optimizations paid off, I created roofline plots for both GPUs:

RTX 4080 Roofline

My optimized kernel sits right at the compute-bound region—exactly where you want to be. The FMA optimizations and early exits pushed us into the peak performance zone.

A100 Roofline

On the A100, the kernel is more memory-bound, which explains why the higher memory bandwidth couldn’t compensate for the lower compute throughput on this problem.

Lessons Learned

1. Know Your Hardware

Understanding GPU architecture—FMA units, memory hierarchy, occupancy—is crucial. Read the architecture white papers. Study the Nsight profiler output.

2. Profile Before Optimizing

I used CUDA Nsight to identify bottlenecks at each stage:

- Initial: Low occupancy (35%)

- After FMA: Better instruction throughput

- After symmetry: Half the work!

- After coalescing: Peak memory bandwidth

- After occupancy tuning: 95% occupancy achieved

3. Problem Structure Matters

The symmetry optimization only worked because I understood the mathematical properties of the Mandelbrot set. Domain knowledge + systems knowledge = winning combination.

4. Sometimes “Cheating” is Just “Being Smart”

Using symmetry felt like cheating at first, but it’s exactly what production optimization looks like. Real-world performance engineering is about finding and exploiting every advantage.

5. Expensive Hardware ≠ Best Performance

The RTX 4080 (consumer GPU, ~$1,200) beat the A100 (datacenter GPU, ~$10,000) on this workload. Match the hardware to the problem, not the price tag to the prestige.

The Full Optimized Kernel

Here’s the final, competition-winning code:

using CUDA

using CUDA.CUDAKernels

function mandelbrot_winner!(output, width, height, max_iter)

idx = (blockIdx().x - 1) * blockDim().x + threadIdx().x

half_height = height ÷ 2

if idx <= width * half_height

x = idx % width

y = idx ÷ width

# Map to complex plane

c_real = CUDA.fma(x / width, 3.5, -2.5)

c_imag = CUDA.fma(y / height, 2.0, -1.0)

z_real = 0.0f0

z_imag = 0.0f0

iter = 0

@unroll 128

while iter < max_iter

z_real_sq = z_real * z_real

z_imag_sq = z_imag * z_imag

# Early exit

if CUDA.fma(z_real_sq, 1.0, z_imag_sq) > 4.0

break

end

# FMA optimized iteration

z_imag = CUDA.fma(2.0, z_real * z_imag, c_imag)

z_real = CUDA.fma(z_real_sq, 1.0,

CUDA.fma(-z_imag_sq, 1.0, c_real))

iter += 1

end

# Exploit symmetry - write to both halves

top_idx = y * width + x

bottom_idx = (height - 1 - y) * width + x

output[top_idx] = iter

output[bottom_idx] = iter

end

end

# Launch configuration

width, height = 4096, 4096

max_iter = 256

output = CUDA.zeros(UInt8, width * height)

threads = 512 # Sweet spot for RTX 4080

blocks = cld(width * (height ÷ 2), threads)

@cuda threads=threads blocks=blocks mandelbrot_winner!(

output, width, height, max_iter

)What’s Next?

This competition sparked my interest in GPU optimization for operations research problems. My current PhD research focuses on applying these same principles to:

- Stochastic linear programming - Parallel scenario evaluation

- Branch-and-bound algorithms - Distributed tree search

- Large-scale integer programming - GPU-accelerated cutting planes

The techniques I learned optimizing a simple fractal are now helping me solve real-world military and aerospace optimization problems.

Resources

Want to try this yourself or learn more about GPU optimization?

Tools I Used

- Julia with CUDA.jl - High-level GPU programming

- NVIDIA Nsight Compute - Performance profiling

- Nsight Systems - Timeline analysis

Key Concepts to Study

- CUDA memory hierarchy

- Occupancy optimization

- Roofline performance model

- FMA (Fused Multiply-Add) instructions

- Memory coalescing patterns

Learn More

- NVIDIA CUDA C Programming Guide

- Julia GPU Programming Documentation

- My detailed Mandelbrot project page

Have questions about GPU optimization or want to discuss competition strategies? Feel free to reach out - I love talking about this stuff!

Interested in the technical details? Check out my full Mandelbrot GPU project with roofline analysis and performance metrics.